International Women’s Day: what does the legal profession look like for women in 2021?

updated on 08 March 2021

After the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act received royal assent in 1919, it began to pave the way for women to become lawyers for the first time in the UK. Much has been achieved since then, but as in many professions, women working within the legal sector still face many distinct challenges.

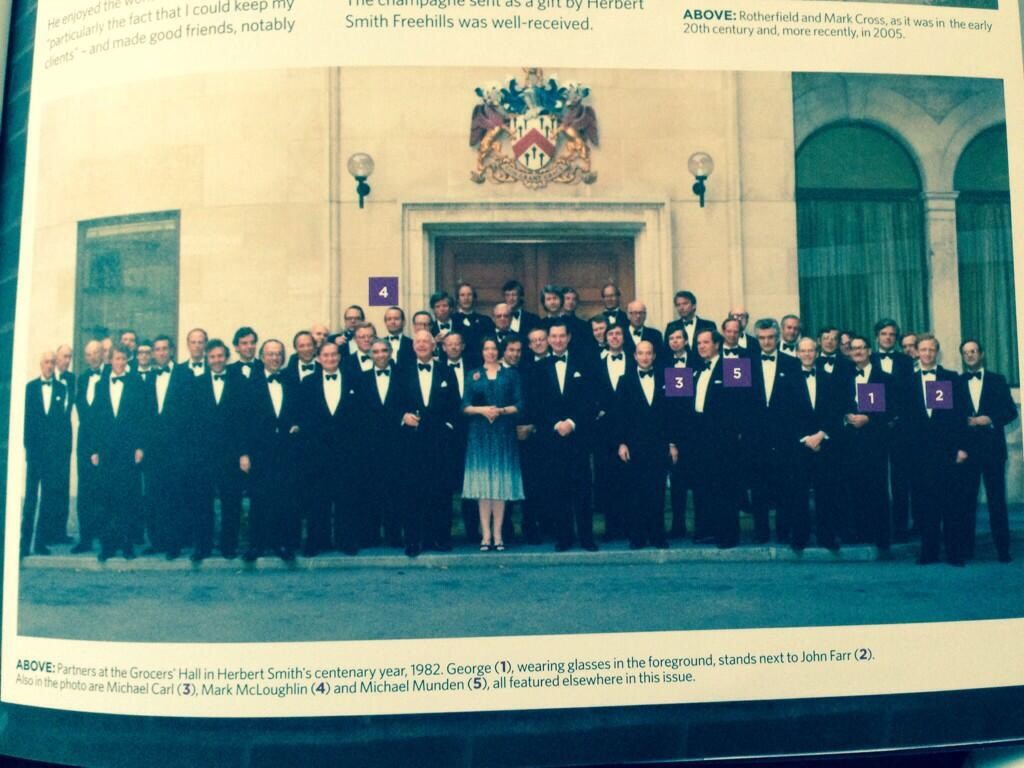

Seven years ago Dana Denis-Smith found the below photograph in a magazine. Its depiction of partners at law firm Herbert Smith in 1982 shocked her: not only does it depict a single, unnamed woman in a mass of be-suited men, but the picture was also taken within her own lifetime. For some this discovery might have been dismissed as a sad reminder of the unequal status quo. However, for Denis-Smith it was inspiration, spurring her to uncover the history of women in the legal profession and to ask whether things really have improved.

The good news is that there have been significant advances. Women couldn’t be members of the Law Society or Inns of Court until 1919 when Parliament forced the doors open with the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act. Unfortunately, even steps as big as this do not mean that the job is done. “Now women can get into the legal profession, but their barrier is to stay and to rise to the top.”

While The First 100 Years chronicles the events of the past, Denis-Smith is clear on what she thinks about the future of women within the legal profession: “It’s very important for me to distinguish what the space is for women now, and to enable women to achieve their ambitions today, rather than fight the battles of the past. By understanding our history, we will be able to map out what we want from the future.”

The Next 100 Years follows the initial project and continues to work towards equality for women in law from all backgrounds.

While there have been significant advances in recent years, the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on gender parity in the workplace cannot go unnoticed. On top of the issues that working full time from home has presented for women, and in particular mothers, in March last year the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) also suspended the requirement that employers must be transparent with their gender pay gap reporting for 2019/20. Although, it is important to celebrate the leaps the legal profession has made to improve gender parity within the workplace, the new issues that threaten to cause a downward slope in progress, such as the pandemic, must also be outlined. There are also countless other factors to take into account when talking about the progress of women in law, including the additional challenges faced by women from LGBTQ+, ethnic minority, disabled or socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Slow progress

Change doesn’t happen overnight. “The first thing that surprised me about doing the project is just how slow the pace really was. The story of the first hundred years is really the story of the last 30 years because nothing much happened for about 60 years”, Denis-Smith notes. “It’s funny because men in the 1920s were so worried about women coming into the legal profession and immediately taking over! But history teaches us that change is very gradual and you really have to build momentum.”

"Now that women are the majority, it’s our chance to define what the legal profession can do, and what the profession of the future will be."

According to the Law Society, women have represented more than 60% of entrants into the solicitor profession since 1990. Yet while just more than half of practising solicitors are female, woman account for only 30% of partners in private practice. The fact that women outnumber men entering the legal profession is significant and Denis-Smith’s message for the next generation is that there is strength in numbers.

“Now that women are the majority, it’s our chance to define what the legal profession can do, and what the profession of the future will be. What will make us proud to be lawyers? I don’t think that question is being asked. It’s not about how we can dislodge power from men, it’s asking what the nature of the power we want is,” she argues. Now that getting into the profession isn’t a problem, Denis-Smith asserts that the focus should move towards creating long-term and fulfilling careers for women.

How has covid-19 impacted women in law?

Following the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic, everyone (where possible) was asked to work from home and the flexible working that many firms were implementing was suddenly forced upon companies overnight. But has the enforced working from home been a positive or negative step for women in the legal profession? What impact could the EHRC’s decision to suspend gender pay gap reporting for 2019/20 have on progress? And what can employers do to ensure their progress isn’t reversed?

Gender pay gap reporting suspended

2020 was set to mark the third year that companies would’ve been required to report their gender pay gap statistics. However, as a result of the pandemic, the EHRC suspended the enforcement of 2019/20’s gender pay gap reporting.

While some employers continued to report, the suspension meant that companies that didn’t publish their reports by the deadline would face no consequences. According to reward management consultancy Paydata, by the end of May 2020 only 5,554 employers had published their report for 2019/20. While more than 2,000 of these were published voluntarily after the suspension was announced, this is a significant reduction on the 10,828 gender pay gap reports in 2018/19.

Despite the suspension, a number of law firms continued to share their gender pay gap reporting. In previous years, many firms have been criticised for excluding partners from their report on the basis that equity partners are not salaried employees and therefore not compulsory to report. This meant that high-earning men were omitted from reports, causing firms to appear more equal than they actually were. These discrepancies were noted by MP and 2019 chair of the Women and Equalities Select Committee Maria Miller who urged firms to be as transparent as possible.

Several law firms, including magic circle firm Clifford Chance, did include partners in their recent reporting.

In Clifford Chance’s 2020 gender pay gap report it revealed that, on a mean basis, women were paid on average 65.7% less than men in 2019 – an improvement of 3.2% on 2018’s figure. Taking the firm’s partners out of the equation, the firm’s report highlighted that, on a mean basis, women were paid on average 20% less than men in 2019 – a 1.8% improvement.

Also including partners in their 2019 report, Freshfields revealed an improvement in its mean pay gap, with women being paid 57.2% less than men in 2019. However, when partners are omitted from the data, this mean average falls quite significantly to 3.8% (5.6% in 2018), showing the continuing prevalence of greater pay disparity at senior levels. That said, the firm also reported the gap for partners only (“covering LLP members and consultants held out as partners”) to reveal a mean pay gap of 10.4%.

The data from both firms that includes partners’ pay shows just how misleading this reporting can be when other firms manipulate the figures by omitting their highest earners.

The EHRC has recently announced a six-month extension to 2020/21’s gender pay gap reporting deadline, so it remains to be seen what the pandemic’s overall impact will be across the United Kingdom.

For young women looking to enter the profession, figures such as these could paint a gloomy picture.

Enforced remote working

While enforced remote working has in some ways offered greater flexibility for parents, school closures due to covid-19 have significantly impacted how women work and the time they have available to dedicate to their work.

A survey of 3,500 families with opposite gender parents by IFS and UCL Institute of Education looked at the way that domestic responsibilities and paid work are being shared across all professions, not just law. Although the results demonstrate that fathers have taken on an increased share of childcare during the pandemic, it’s important to note that this time remains 2.3 hours less than mothers. The report also indicates that “mothers in two-parent households are only doing, on average, a third of the uninterrupted paid-work hours of fathers”.

Further, two Next 100 Years surveys of women in law from May and October 2020, continue to demonstrate the difficulties that remote working and school closures have had on women in the legal profession, as well as the impact that it has had on wages and work. Of the 900 women surveyed in May, 350 had school-aged children at home, with 91% of them reportedly taking on extra childcare and home-schooling responsibilities, while 32% revealed that they had been forced to reduce their working hours. On top of this just under half said they were taking on more childcare responsibilities than their partner, reinforcing the findings from the IFS and UCL Institute of Education survey.

Meanwhile, 65% of the 870 women from the survey in May said that they were “concerned that the lockdown was exaggerating existing inequalities between men and women”.

The more recent October survey continues to depict a worrying picture of the profession post-pandemic. With incomes cut to enable firms to weather the pandemic’s impact on business, 24% of 419 surveyed women said that their incomes were yet to return to pre-covid levels, 19% were still working reduced hours, while more than 50% voiced concerns that women were being “disproportionately impacted by cuts and redundancies”.

Offering an insight into the impact of the pandemic on women in the UK, these statistics paint a bleak picture and serve to remind employers how much more work needs to be done to reach gender parity.

What should employers do?

Flexible working – an obvious solution?

So, what steps can law firms take to support women in their businesses? Looking at the make-up of many law firms, it’s clear that there is a distinct level at which many women disappear after having children. Until issues of childcare and flexibility are addressed, women can too easily be held back from the top – an issue which has only been exacerbated further by lockdown, school closures and the responsibility divide between parents.

Divorce lawyer Ayesha Vardag recently told The Times that “It’s like [maternity rules have] been set up by men in the 1950s. You go off and do your stuff with your baby and you should be back with your baby all of the time and, if you’re coming back, you better come back full time or we’re not interested.” Her argument that the future of maternity leave is to encourage women to go back to work as soon as possible, even if it’s just for half a day a week, might raise a few eyebrows, but it also suggests that there must be a formal element of flexibility for parents in the workplace. In fact, Vardag’s own experiences of maternity leave influenced her decision to offer employees at her firm superb childcare when returning to work at any stage between three months and a year.

At 2019’s LawCareersNetLIVE event, the panel of partners discussed the importance of work-life balance for everyone, not just parents. Speaking about flexible working, Sarah Porter from Baker McKenzie stated: “I think the focus is always on children and it shouldn’t be. People have other hobbies – for example, they may have choir practice or play football. Everyone has a right to think about what is immoveable in their life”. She added: “Ultimately, we work to have a life.”

‘Flexible working’ or ‘agile working’ have been buzzwords in the industry for some years now and, prior to the pandemic, several big names had already shown their commitment to embracing it.

In 2016 international giant Baker McKenzie rolled out agile working across its global network, while in 2017 Morgan Lewis allowed its UK and US lawyers to work from home for up to two days a week. International firm Norton Rose Fulbright (which won the Commendation for Diversity award at the LawCareers.Net Training & Recruitment Awards in 2020) recently set out its new global gender diversity targets across all levels as part of its commitment to diversity and inclusion: “In 2014, the firm set itself a target of achieving 30% female partners worldwide and 30% female partners on all board and management committees by 2020. In January 2021, 53% of global partner promotions were women. In February 2020, the firm announced its new aspirational global gender diversity targets across all levels: a minimum of 40% women, a minimum of 40% men, and 20% flexibility to be fully inclusive. As of February 2021, there are 28% female partners worldwide, the Global Executive Committee has 40% women and the Global Supervisory Board has 32% women. In the UK, 56% of the combined workforce and partners are women; 29% of partners are women; 58% of associates are women; and 56% of trainees are women.”

The firm also revealed plans to introduce a new hybrid working policy across Europe, the Middle East and Africa once the pandemic has passed, enabling its staff to work remotely for up to 50% of their time. The policy will continue to be developed in line with individual, team and client needs: “We believe that high performance can only be achieved in a culture where unique ideas and diverse perspectives are valued and encouraged. We look for individuals with the ability to approach challenges, solve problems and make decisions and see opportunities differently. Embracing this means we attract and retain the best talent and provide our clients with the most considered and innovative advice.”

Following the move to remote working as a result of the covid-19 pandemic, many other firms have adopted new agile working policies and City firms have started cutting office space, as lawyers forecast remote working to become the new norm. Both Linklaters and Taylor Wessing are due to implement agile working strategies. It will also be important for firms to consider how these agile working strategies can be implemented in a way that ensures women are still being exposed to the same opportunities as their male counterparts.

For more insight into what steps firms can take to support and promote women, the Government Equalities Office put together a guide which sets out its advice on reducing the gender pay gap and improving gender equality, including:

- encouraging salary negotiation;

- using skill-based assessment tasks in recruitment;

- setting internal targets; and

- encouraging the uptake of Shared Parental Leave.

Entering the legal profession – what do students think?

While many practising lawyers balance work and family life, it is also important to consider the barriers that many women face before they have even qualified. BPTC graduate Marwa Tariq outlined the obstacles she encountered as a student while also raising a family: “The biggest challenge I faced while studying law as a parent was ensuring I had childcare arrangements during the evening networking events, classes or qualifying sessions for the BPTC – or really anything that involved the evening! Law events scheduled for the weekends or evenings make it really difficult for those who have caring responsibilities to have access to a breadth of opportunities that can otherwise help a person get ahead in the legal profession.”

Firms and education providers must do more to support women aspiring lawyers, and aspiring lawyers with families and additional caring responsibilities as they embark on their journey into the legal profession. As the world becomes increasingly virtual, Marwa urges firms and law schools to provide “more work and academic opportunities online”.

She added: “This will allow women with children to have more flexibility in managing their time and saving on expenses, while also helping to manage the stress relating to arranging childcare.” We also asked aspiring women lawyers whether they consider their gender to be an obstacle to pursuing a legal career. It was clear from the response, that the barriers women face are already being considered by the next generation of lawyers.

First-year LPC student Neide Lemos looks ahead to her future career: “As aspiring women lawyers, the first thing we usually consider is whether progression into senior roles will be possible alongside raising a family.” Since 1990, and following the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act receiving royal assent in 1919, women have represented more than 60% of new entrants into the legal profession, according to the Law Society. That said, the image painted of the legal profession for aspiring women lawyers setting out on their journey is still relatively male dominated. Neide explains that “even the textbooks rely on judgments made by men. We need to improve flexible working and accessibility to leadership. Progress has been made but there is still a long way to go.”

Echoing Neide’s point that the profession still appears male dominated, despite the numbers, international relations graduate Harriet Herbert opened up about her journey: “As a woman entering commercial law, I face the struggle of proving that I meet a benchmark that is set by men, for men.”

Harriet also emphasises the significance of a firm’s diversity and inclusion policies: “As an LGBT woman and aspiring lawyer, gauging the authenticity of a law firm's policies on diversity and inclusion is an additional step that I take in the application process. When I first began exploring a career in law, I was intimidated by my preconceptions of law firms being very 'traditional' or 'conservative'. I think this is probably something that concerns a lot of aspiring lawyers from underrepresented groups.”

Future trainee solicitor and GDL graduate Olivia Atkinson reinforces the need for more flexible opportunities for women in law: “It is the responsibility of the profession to encourage gender equality and to provide the opportunities that determined women seek”.

One question that undergraduate student and founder of When Life Gives You Lemons Dunja Relic always addresses to female trainees at events is “how do you manage to effectively balance work and family life? Is it actually possible for women to have both?”

She described some of the responses she has received in the past as “horror stories” – for example “some women who had worked so hard to get up the ladder to have had it all stripped away when they choose to start a family.”

Dunja added: “The facts and figures speak for themselves – there is a lack of women in senior positions. In a strange way, I think the pandemic has aided us in realising just how agile work can be in the legal profession. It will be interesting to see how this time will shape the future of the legal sector, particularly for women. I think obstacles to pursuing a legal career are more evident when we look at gender in an intersectional way, coupled with other socio-economic characteristics such as race, migration status and disability. There is still a big gap in achieving equality of opportunity.”

Firms must demonstrate a commitment to improving the support and opportunities they offer to women from all backgrounds at the very outset of their careers in order to retain women at more senior levels. While it is understandably hard work to progress up the legal profession’s career ladder, having to work 10 times harder than your male counterparts to get to the same level, should not be at the forefront of a junior lawyer’s mind. If firms don’t highlight such a commitment, they could put off an entire generation of women from applying, therefore exacerbating the situation.

Structural problems

The main obstacles in women’s progress to senior positions are still “rigid and inflexible structures” argues Denis-Smith. One of her solutions is an end to the ‘salaried partner’ position, where senior women often find themselves side-lined. A salaried partner is technically a non-equity partner – this means that although they earn the salary of a partner, they have no voting power and are therefore not adequately represented at the top.

For Denis-Smith another key solution would be to change attitudes towards assessment during training schemes. She questions how potential is measured in candidates, arguing that women are misjudged and incorrectly assessed on schemes. “We need to change the idea of leadership within the profession and how we measure it from the point of entry in the law firm”, she maintains.

We need to change the idea of leadership within the profession and how we measure it from the point of entry in the law firm

These kinds of structural changes are not easy to implement and may require employers to make a concrete commitment to gender equality. Quotas are controversial but they do force employers to directly address imbalances and make strides in order to progress quickly. Denis-Smith is an advocate for quotas, arguing that self-regulation can only take us so far. The point has been made by several other high-profile lawyers and campaign groups, including the Fawcett Society. Its former chief executive, Sam Smethers, told The Guardian that “Equality won’t happen on its own. We have to make it happen.”

Moving forward to an equal picture

The Law Society has been taking stock of the situation in the legal profession, surveying lawyers, judges and legal support colleagues and holding roundtable discussions about issues affecting women. Themes raised include unconscious bias, women from ethnic minority backgrounds, flexible working, and standards of behaviour.

When she was in office in 2019, former Law Society President Christina Blacklaws stated: “For future female solicitors to reach senior leadership positions at an equal rate to men, the work culture of law firms needs to adapt to suit both men and women. As a profession which strives to uphold justice, the legal sector needs to be at the forefront of the fight for equality in the workplace.”

With Law Society President David Greene set to stand aside in March, Vice-President Stephanie Boyce will become the Law Society’s latest 177th president – making her the second in-house lawyer and the first ethnic minority president to be elected in the society’s 200-year history. Boyce has pledged to continue with former Law Society President Blacklaws’ work, while also expanding its reach: “There is, however, the need to extend this work to other areas and address the general issues that exist such as inclusivity for potentially disadvantaged or minority groups – including BAME, the disabled, those from the LGBT+ community and from a low socio-economical background.”

In an interview with The University of Law Boyce said: “My election is likely to impact how potential candidates are perceived in the future, which for me is one of the most valuable outcomes changing what people envision when they think of what leaders should look and sound like.”

She added: “I want to continue to be part of a forward-looking body that advocates and promotes change, challenges and influences whatever the future may hold for our profession.”

Boyce’s advice to newly qualified female solicitors is to join divisions, such as The Women Lawyers Division, and “take advantage of networking opportunities locally and nationally, and have your voice heard as we begin our march towards the next 100 years of women in the law.”

As Denis-Smith points out, progress is slow. Some firms are getting it right and making active decisions about the importance of supporting the women in their businesses. But it’s also clear that more must be done as we move away from the photograph that she discovered in 2014. The legal landscape is gradually changing. But, in the age of increasing collective consciousness about issues of diversity and equality, the question remains: how many more years will it take to get a truly representative picture?

Bethany Wren and Olivia Partridge are, respectively, content and events manager and content and engagement coordinator at LawCareers.Net.